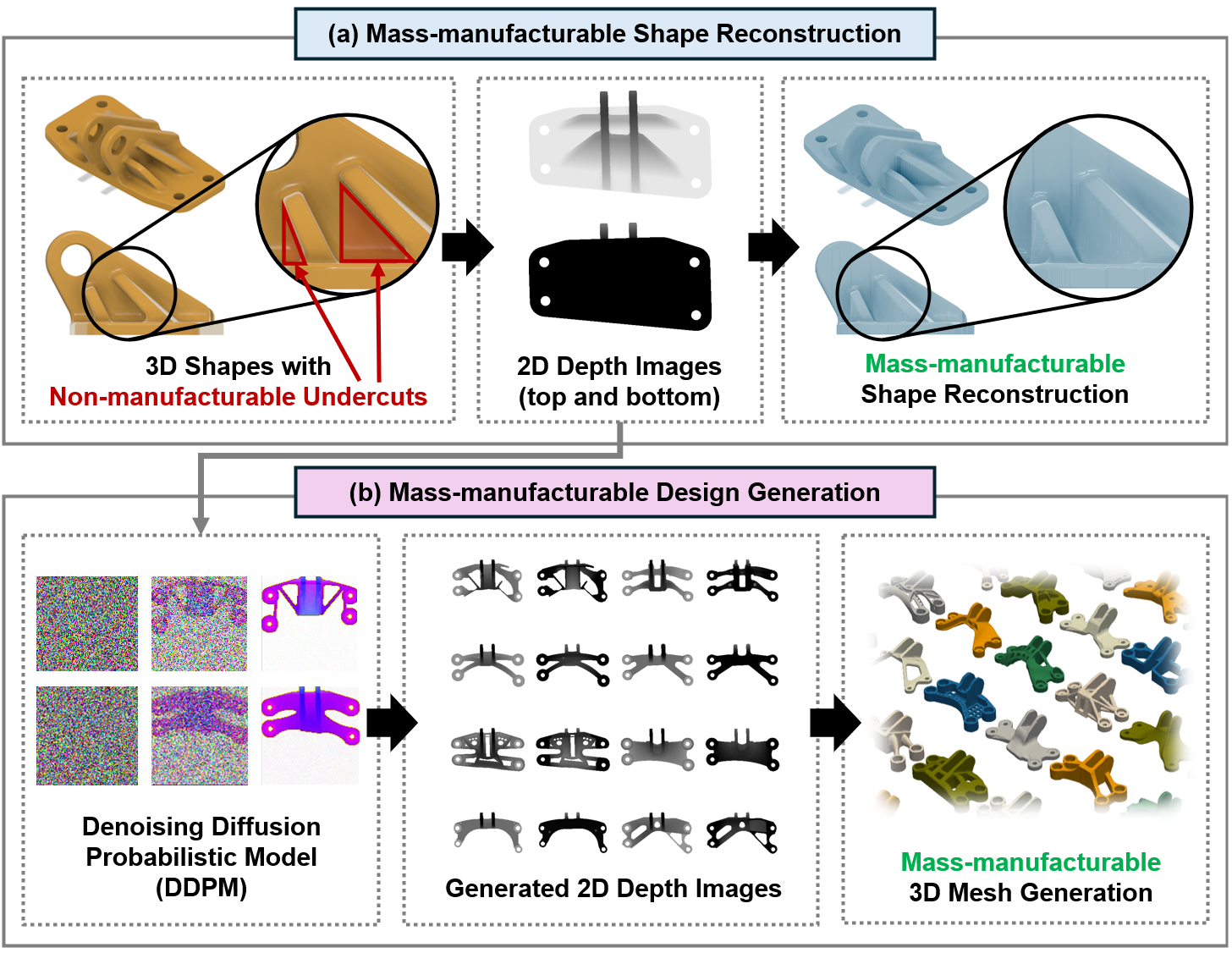

Deep Generative Design for Mass Production

How a simple 2D representation guarantees that generated 3D shapes can be mass-produced

The Challenge

Imagine you’re designing a structural bracket for an airplane. Modern AI can generate remarkably efficient 3D shapes through topology optimization and generative design. But here’s the problem: these generated shapes often can’t be manufactured at scale.

Mass production methods like die casting and injection molding have strict requirements. The mold must be able to separate from the part. There can’t be undercuts or complex internal cavities. The shape must have draft angles for release.

Traditional deep learning-based generative design ignores these constraints, producing organic shapes that work beautifully in simulation but require expensive, slow manufacturing processes like 3D printing.

The Question: Can we teach neural networks to generate 3D shapes that are inherently manufacturable from the start?

The Key Idea

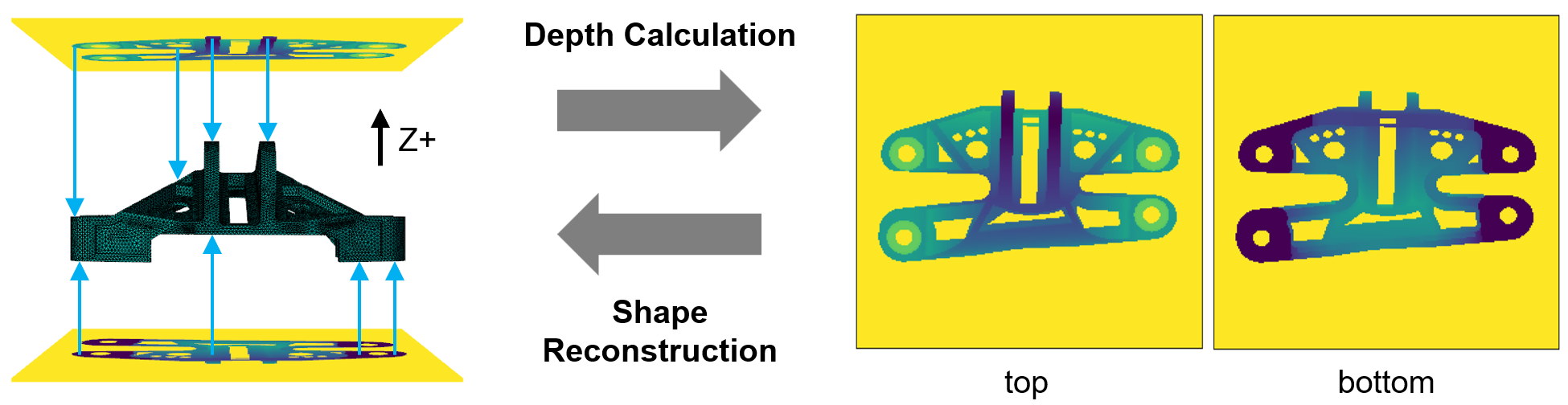

Our approach is deceptively simple: convert the 3D design problem into a 2D problem.

Instead of generating complex 3D geometry directly, we:

- Represent 3D shapes as depth images — a simple 2D projection where pixel brightness encodes height

- Train a generative model in 2D — much easier and more efficient than 3D generation

- Reconstruct back to 3D — a deterministic mapping from depth to geometry

Why 2D?

Working in 2D provides several advantages:

- Simpler learning — 2D CNNs are well-understood and efficient

- Faster generation — 2D operations are computationally cheaper than 3D

- Higher efficiency — 2D models are much faster to train and converge more easily than 3D methods like point clouds or voxels

But the real breakthrough is what this representation enables for manufacturing.

Manufacturing Constraints

Here’s the key insight: depth images naturally encode manufacturing constraints.

A depth image can only represent shapes that are visible from a single viewpoint — shapes that could be formed by a mold pulling away in one direction. This is exactly what die casting and injection molding require.

By choosing to work with depth representations, we’re not just simplifying the problem. We’re embedding the manufacturing constraint directly into our data representation. The network literally cannot generate shapes that violate the manufacturability requirement.

Core Innovation: The constraints don't need to be learned or enforced — they're structurally guaranteed by the representation itself.

How Generation Works

So how do we actually generate new designs? We use a Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM)—the same family of models behind image generators like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E.

The process works in two phases. During training, the model learns from a dataset of existing bracket designs (converted to depth images). It learns to reverse a noise-adding process: given a noisy depth image, predict what the clean version should look like. During generation, we start with pure random noise and iteratively denoise it, step by step, until a coherent depth image emerges. The model has learned the statistical patterns of valid bracket designs, so the generated depth images look like plausible new brackets.

To help the model generate high-quality designs, we train it on three channels: top depth, bottom depth, and an edge map (detected using a Canny filter). The edge channel helps the model understand important boundaries and ensures the top and bottom surfaces connect properly. This third channel is optional—the model can work with just two depth channels, but adding edges improves generation quality. Only the depth channels are used for 3D reconstruction.

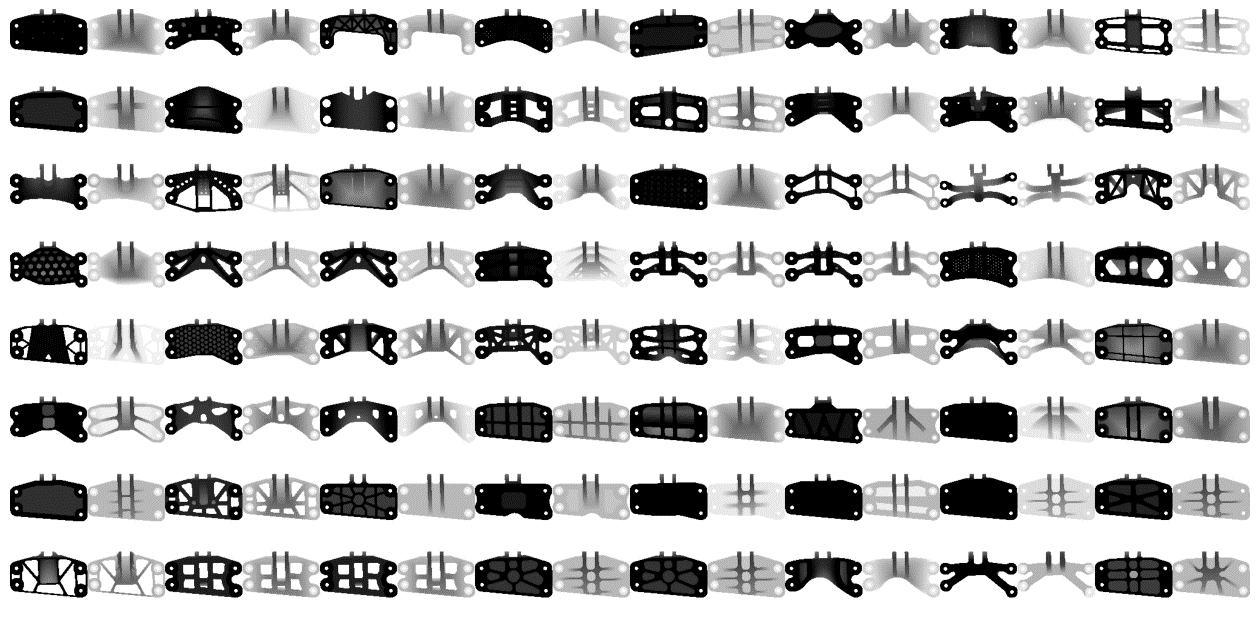

Generated Designs

Here are 16 bracket designs generated by the diffusion model—each one is a novel design that never existed in the training data. No cherry-picking was done: these are 16 consecutive samples straight from the model, converted to 3D meshes.

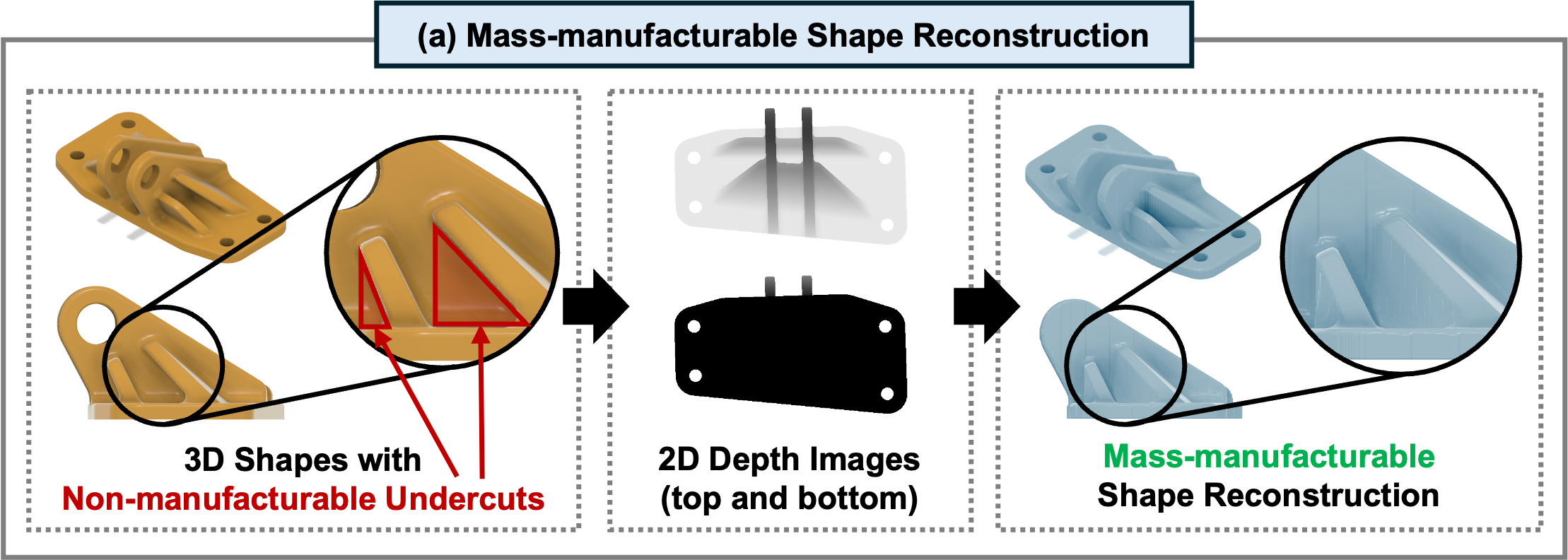

Enforcing Manufacturability

Let’s examine how the depth representation enforces manufacturability. Below is an interactive comparison showing an original bracket from the SimJEB dataset (left) and the same shape after passing through our 3D → 2D → 3D reconstruction pipeline (right).

Rotate and zoom both models simultaneously to explore how well the reconstruction preserves the original geometry while guaranteeing manufacturability.

Notice how the reconstructed model:

- Preserves overall structure — the key load-bearing features remain intact

- Smooths impossible details — fine features that can’t be manufactured are simplified

- Maintains symmetry — design intent is preserved in the transformation

Why does it look blocky? The reconstructed model appears pixelated because it was generated from a low-resolution depth image. This is a visualization choice, not a limitation of the method—using higher resolution images or upscaling produces much smoother results suitable for production.

Adding Draft Angles

For real-world manufacturing, parts also need draft angles—slight tapers that allow the part to release smoothly from the mold. Our method can apply these automatically.

Why This Matters

This approach bridges the gap between AI-driven generative design and practical manufacturing:

| Traditional Approach | Our Approach |

|---|---|

| 3D generation (slow, memory-intensive) | 2D generation (fast, efficient) |

| Manufacturability checked after | Manufacturability guaranteed by representation |

| Often requires manual rework | Designs are more production-ready |

| Typically limited to 3D printing | Compatible with die casting & injection molding |

For industries that rely on mass production — automotive, aerospace, consumer electronics — this means AI-generated designs can go straight from algorithm to factory floor.

Current limitations: The method currently supports single-direction mold release. More complex geometries requiring multi-part molds or internal channels would need extensions to this approach.